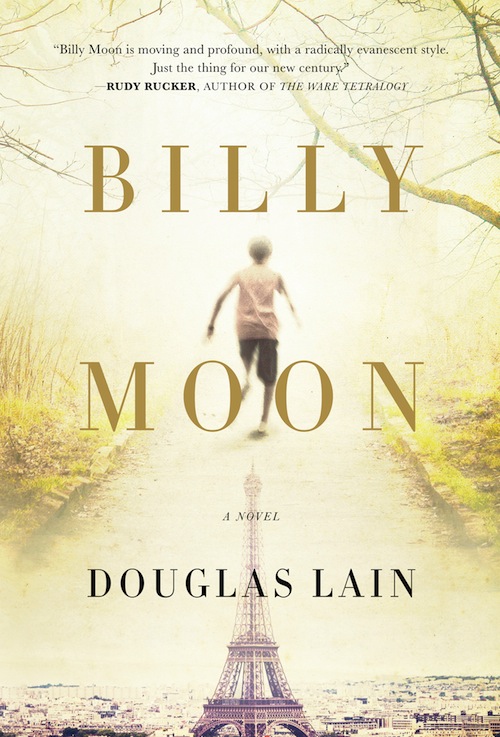

Take a peek at Douglas Lain’s debut novel, Billy Moon, out on August 27:

Billy Moon was Christopher Robin Milne, the son of A. A. Milne, the world-famous author of Winnie the Pooh and other beloved children’s classics. Billy’s life was no fairy-tale, though. Being the son of a famous author meant being ignored and even mistreated by famous parents; he had to make his own way in the world, define himself, and reconcile his self-image with the image of him known to millions of children. A veteran of World War II, a husband and father, he is jolted out of midlife ennui when a French college student revolutionary asks him to come to the chaos of Paris in revolt. Against a backdrop of the apocalyptic student protests and general strike that forced France to a standstill that spring, Milne’s new French friend is a wild card, able to experience alternate realities of the past and present. Through him, Milne’s life is illuminated and transformed, as are the world-altering events of that year.

Part One

1959–1965

In which Christopher Robin fails to escape his stuffed animals, Gerrard goes to the police museum, and Daniel is diagnosed with autism

1

Christopher was thirty-eight years old and still hadn’t managed to escape his stuffed animals. Worse, the neighborhood stray, a grey British Shorthair, was scratching at the entrance of his bookshop. Chris looked up to see the cat making no headway on the glass but leaving muddy prints under the sign that was now flipped so that the CLOSED side was facing out for passersby to read. The cat’s scratching made a repetitive and grating noise that reminded Chris of a broken wristwatch.

It was October 2, 1959, and Christopher was up early. It was his usual practice to enjoy these solitary early hours in the bookshop. He quite liked waiting for the teakettle to sound, looking out at the mist over the River Dart, and listening to the silence that seemed to radiate from the spinner racks full of paperbacks. He had the novel On the Beach by Nevil Shute open by the cash register and he was skimming it. The story had something to do with a nuclear war and a radioactive cloud, but the details weren’t getting through to him. He just had twenty minutes or so before Abby would be awake, and he decided not to waste them on another literary apocalypse.

Chris had been getting up earlier and earlier, spending more and more time on the inventory sheets, keeping track of the invoices, and taking care of that local stray cat. Hodge—Christopher had named him Hodge—was an abandoned tabby actually, and not a British Shorthair at all. Hodge had been content to live over the bookstore and eat what Chris fed him, usually fat from a roast or bits of fish, outside on the boardwalk. At least, that had been the arrangement for nearly six months. Lately Hodge had been a little more demanding. He had, on occasion, even made his way inside the shop.

When the kettle sounded Chris poured the hot water into a bone china pot ornamented with blue flowers, waited for his breakfast tea to steep, then poured a cup and added cream and sugar. Only after all of this did he give in to the sound at the door, but by this time, Hodge had changed his mind. Chris opened the door and the cat wandered away, across the boardwalk and into the weeds. Hodge hadn’t really wanted in at all, but maybe had just wanted Christopher’s company out in the grey mist of the morning. It was impossible to say for sure.

He stepped back into the shop, slowly wandered down the main aisle, taking a moment here and there to note what books were still in place, which books had been on the shelf the longest, and when he reached the counter he wrote down the titles. He checked the ledger for the previous day and saw that the list of old books hadn’t changed. J. P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man and Colin Wilson’s The Outsider had been big sellers for several years, but perhaps Devon had run out of angst because he had three copies of each gathering dust.

Then Hodge was at the side window. The cat was sitting on a waste bin under the store’s green-and-white awning and was scratching away again, leaving more muddy paw prints.

Chris stepped outside again, onto the boardwalk, and walked around the corner of the shop to the waste bin. He reached down, hooked his hand around the cat’s midriff, and carried him like that, with his legs and paws dangling, into the shop.

“I’ll make up your mind for you,” Chris said.

There was no point in trying to discipline a cat. You could try scolding, even give the animal a good wallop, but all that would accomplish would be a reaction, maybe get you scratched. The cat might scurry off between the bookshelves, look at you indignantly, perhaps even feign indifference, but the cat would never behave differently. Cats merely did what they did.

There was a stack of boxes behind the counter, a new shipment of children’s books, but Chris hesitated to open them. For a moment, before opening the first one, Christopher remembered how the shop, his Harbour Bookshop, had looked before the first shipment of books arrived. When the shelves were bare they’d reflected the light coming in and the shop had seemed positively sunny. There was nothing in the bookstore but light, shadow, and the smell of sea salt.

Christopher opened the box of books and then felt a familiar anger welling up in him.

“Abby, you bloody well know that we don’t sell Winnie-the-Pooh,” he shouted into the stacks. His wife was upstairs, either still in bed or in the lavatory. She was spending a great deal of time on the toilet, even more than he’d originally expected when she’d told him she was pregnant. Wherever she was she surely couldn’t hear him shout, but he was tempted to shout again, only louder. He let out a long sigh instead.

Christopher made his way up the stairs and called out again.

“Shall we ask the Slesingers and Disney to become partners in our bookstore? Shall we sell dolls and toys and records, all the Pooh paraphernalia? We could probably forgo selling any other books at all. Shall I dress up in plus fours for the tourists? Do you want to start calling me Billy?”

Nobody called Chris “Billy” or “Billy Moon” anymore. It was a relic, a variation on the name his father had given him when, as a very young boy, Chris had been unable to properly pronounce their surname, and had declared the whole family to be Moons. Over the years all of Chris’s childhood nicknames—Billy, CR, and Robin—had fallen to the side. He’d volunteered for service during World War 2, and he’d shaken loose of his childhood, or so he’d hoped.

“Did you let that cat in again?” Abby stood at the top of the stairs in her nightgown with her fingers up to her nose. She was holding back a sneeze.

Was her belly getting bigger? Christopher thought he could just see a difference, a slight curve underneath her billowy silk gown.

“I found the Pooh books,” Christopher said.

“You think our customers shouldn’t find any part of your father’s work in our store?”

“I’m not interested in selling that bear.”

“You and your mother have a lot in common.” Abby turned away, disappeared around the corner, and Chris returned to the stacks and put three copies of The House at Pooh Corner on the shelf. Then he taped up the rest in the box they’d arrived in and wrote out the address for his distributor on a sticky label. He’d send these back.

Christopher opened another box of books and found Dr. Seuss inside. He ran his finger along the spines as he placed the books on the handcart, and then he looked again at The Cat in the Hat. He looked at the red-and-white striped top hat, at the umbrella the cat was holding, and the precariously placed fishbowl, and remembered or realized the truth about the stray cat he’d been feeding and the truth felt odd to him, something like déjà vu.

Hodge was neither a British Shorthair nor a tabby, but a stuffed toy. Abby had purchased a black cat with synthetic fur and straw inside for the nursery, for the boy they were expecting. Hodge was made by Merrythought and Christopher picked him up from the bookshelf where he’d left him.

Chris felt he’d slipped between the cracks. The moment seemed to hold itself up to him for his inspection. Abby had been sneezing, threatening to sneeze, because of this toy?

Christopher looked from the cash register to the front door, examined the spot where Hodge had been scratching, at the muddy paw prints there, and then went to fetch a wet rag. After he’d washed the glass on the door and taken care of the shop’s side window he washed out the rag in the kitchen sink, wrung it thoroughly, and hung it on the rack under the sink to dry.

He approached the door again, turned the sign around so that it now read OPEN to passersby.

Hodge was waiting for him by the register. He picked the cat up and turned him over in order to look at the label.

MERRYTHOUGHT, HYGIENIC TOYS,

MADE IN ENGLAND.

Chris took the toy cat with him when he made his way upstairs to ask Abby what she’d meant. He tucked the toy under his arm and started up, taking the first two steps in one go, jumping, and then stopping to get a hold of himself. He would just ask her what she’d meant about the cat, ask what cat she’d been referring to, and that was all, no need to panic.

The bed was still unmade and Abby was at her vanity, she had one of her oversized maternity bras half on, draped over her shoulder but unclasped, and was brushing her auburn hair. When he stepped up to the table and put the toy cat down next to a canister of facial powder, she put the brush down and started tying her hair back into a bun.

“Did you ask after Hodge?”

“Hodge?” she asked.

“Did you ask me if I was feeding the stray cat?”

“Were you?”

This wasn’t very helpful so Chris turned Abby to him, away from the mirror, and made her listen to him as he asked it again.

“Did you ask me if I was feeding the cat?”

“Yes. Did you feed him?”

Chris picked the Merrythought toy up from the vanity and held it to her, watched her eyes as she looked it over, checked to see if he might catch some sort of comprehension there.

“This cat?” he asked.

Abby took the toy from him, turned it over in her hands, and then put it down on the vanity and returned to tying back her hair. He waited for a moment, giving her time.

“I’m not sure I understand,” she said. “Is there a cat? I mean, is that the cat?”

This was the question Chris wanted to answer, but now that she’d asked aloud the answer seemed further from him. If there was a cat named Hodge how had he come to mistake this toy for him, and if the toy was Hodge then what animal had been eating the table scraps he’d left out? Chris tried to explain the problem to her, he retraced his steps since he’d gotten up, but she was as mystified as he was and suggested that there was nothing for it but to have breakfast.

They had fried eggs, fried mushrooms, potatoes, and more tea. Christopher put jam on wheat toast, but afterwards he couldn’t help but bring it up again. It was still relatively early; perhaps they could close for a bit and take a walk? Maybe they could track down the real cat? They might take the trouble to find Hodge and put it to rest.

They took the toy cat with them when they went out. Chris wanted to show the toy around while they looked for Hodge, but the boardwalk along the embankment was still empty. The Butterwalk building was closed but Christopher saw that there were lights on inside and so he went ahead and called “kitty, kitty, kitty” under the fascia. He walked along the line of granite columns, looking behind them and around them hopefully, but he didn’t find a real cat there either.

They looked in the windows of the Cherub Pub and Inn. Chris had the impression that the owner, an older man named William Mullett whose family had run the pub for generations, had also taken pity on Hodge over the last few months. He’d seen William feeding Hodge raw halibut from the inn’s kitchen, and he wondered why the cat ever ventured over to the Harbour Bookshop given how he made out at the Cherub. They were open for breakfast, so he and Abby ventured in and found William sitting at reception.

“Morning, Christopher,” William said. He was a bald and round man who’d been in the first war but otherwise hadn’t seen much outside of Dartmouth. “Morning, Abby. What brings you two round this morning? How are the books?”

“Morning, William,” Christopher said. He looked at Abby and then back at William and wondered what he wanted to say or ask.

“We’ve come to ask after a cat,” Abby said. “Christopher has had some difficulty with a tabby.”

“An English Shorthair,” Chris said.

William nodded. “I’ve been meaning to stop by your shop. There might be a new hardcover I’d be interested in.”

“Ah, yes. Well, what brings us in this morning is this stray cat I’ve seen you feeding. He might be a tabby or an English Shorthair. I called him Hodge.”

William considered this. “Ah.”

“The question is whether you’ve seen him. I mean, am I right? Have you been feeding him?”

“That cat?” William asked. He pointed to the toy Chris was still carrying and Chris held the thing up.

“Did you just point to this cat? This one I’m carrying?”

“That’s Hodge, isn’t it? Yeah?”

“You think this is Hodge?”

William shrugged and then turned to fiddling with a few papers on his desk. He looked down at the list of guests, touched the service bell, and then looked up at them again and nodded. “Yeah, that’s Hodge?”

Christopher put the toy down gently in front of William and then turned it over for him so he could see the tag. He leaned over toward the innkeeper and asked him again.

“Are you saying that this toy cat is Hodge? This is the cat you’ve been feeding?”

William picked the black cat up, turned it over a few times, and then put it back down again. He took a letter opener out of his top drawer and cut the seam in the cat’s belly. William pulled out straw.

“No. This can’t be him,” he said.

Christopher told William that he’d had the same misperception this morning, that he was wondering if there had ever been a cat, and then asked William why he’d cut the toy open.

“Just thought I’d see,” William said. “But you’re right, Christopher. That’s not the cat we know. Did you get that one for the baby?”

Later that afternoon Chris wore his Mackintosh raincoat and his Wellington boots when he left the Harbour Bookshop just to go for a walk. It was around three o’clock in the afternoon, and since there hadn’t been a customer since lunch he decided to close the shop early and see where the narrow streets and paths in Dartmouth would take him. He needed to get out into the world, get away from the stale air inside his shop. He’d been confused was all, but a walk would fix that. He would go for a walk and know that what he was seeing in his head matched up with the world outside.

Christopher called “kitty, kitty” just a few times, and when no cat came to him he breathed in and tried to enjoy the moist air as he stood on the boardwalk. He frowned when he looked out at the water and spotted a bit of rubbish floating in the Dart. He’d have to go down to the dock, lean out between a small red leisure sailboat and an old fishing boat that looked like it might rust through, and fetch it out.

It wasn’t until he was on the dock and lying on his stomach, halfway eased out over the water, that he wondered if there really was something out there. He stretched until the wet paper wrapper was just within his reach and caught it with his index and middle finger. It was a Munchies candy wrapper, bright red and a bit waxy.

Returning to the shop, Christopher turned the lights on and went to the trash bin behind the front counter. He examined the register to make sure it was locked properly. He wanted to go back out, intended to lock up for the rest of the day, but as he was checking that everything was settled behind the register the front door opened and a customer entered. It was William.

“Afternoon, Christopher.”

“William. Glad to see you. Did you remember anything more about that cat?”

“What cat is that, Christopher? The toy cat? No, no. I’ve come in to look at your books.”

William made his way into the stacks, then came over by the register. He moved his lips as he read Eugene Burdick’s The Ugly American and leaned on the spinner rack.

“Uh, William?”

“Yes, lad?”

“The spinner won’t bear up. It’s not meant to hold more than books.”

There were rules to running a bookstore, rules to being a customer, and sometimes it seemed William didn’t understand any of them. A few weeks back he’d come in at two o’clock, found a copy of a book that seemed interesting to him, and spent three hours leaning against the stacks and reading Charley Weaver’s Letters From Mamma. Now William was going to keep Christopher in the shop for another afternoon of browsing.

He wanted to ask the old man again about Hodge, but he didn’t know what to ask. The two of them had made the same mistake, or had had the same hallucination, but how could they talk about it or make sense of it?

While he waited for William to finish up he thought of the Munchies wrapper in the bin. Someone had just tossed their garbage into the Dart. People were losing their grip on the niceties that made life work in Devon. It had something to do with pop music and television. He considered the Munchies wrapper and wondered if it was, in fact, still there. He tried to remember what was on the Munchies label. Something about a crisp at the centre and toffee?

Christopher reached under the register, into the waste bin, and was relieved to pull out the Munchies wrapper. It was still there.

“ ‘Milk chocolate with soft caramel and crisp biscuit centre,’ ” he read.

William moved away from the novels to the aisle with popular science books. He thumbed through a guidebook for mushroom identification and then picked up Kinsey’s book Sexual Behavior in the Human Male.

“That one is for reading at home I think. Would you like it?” He dreaded the idea of old William standing around in the store for hours reading about erections, fellatio, and masochism.

“This fellow died young, didn’t he?” William asked.

“Depends on your definitions.”

“Can’t bring this one home. That would be a scandal. Besides, I wouldn’t want the wife reading up on all the ways I was deficient.”

“I see. Is there anything then? You’d said there was a book you wanted?”

William looked up at Christopher, a bit surprised. “You’re eager to look for Hodge again, Chris?”

Christopher let out a breath and then told William no. He wasn’t going anywhere. Then, rather than continue on with that, Christopher held the candy wrapper up in the light and considered it again. He put the candy wrapper back into the trash bin, pushed the bin under the register and out of view, and then took it out again to check the wrapper was still there and still the same. He picked up the trash bin and repeated this several more times. In and out. It was somehow satisfying. He felt reassured each time, back and forth. He felt relieved until it dawned on him what he was doing.

Chris was acting out a scene from one of his father’s stories. In the first Pooh book there had been a scene just like this only with a popped balloon and not a Munchies wrapper. In the story the stuffed donkey, Eeyore, had felt better about his ruined birthday once he realized that a deflated balloon could fit inside an empty honey jar. And now, in an effort to prove that he was sane, Christopher was repeating this same simple action.

“ ‘He was taking the balloon out, and putting it back again, as happy as could be,’ ” Christopher said.

“What’s that?” William asked.

How had Christopher arrived at this? He was reenacting his father’s stories in order to convince himself that the world was real?

“Maybe I could find a secret spot for it,” William said.

“What’s that?”

The old man put Kinsey’s book on the counter. And Christopher was struck by something like déjà vu for the second time that day.

The red-and-white cover, the way the words “Based on surveys made by members of the University of the State of Indiana” fit together above the title, it matched the design on the Munchies wrapper. Christopher took the wrapper out of the waste bin and unfolded it on the counter so it was set down flat next to Kinsey’s red book.

“‘Milk chocolate with soft caramel and crisp biscuit centre.’ ” He read the words again.

“What’s that?”

Christopher felt some anxiety looking at the juxtaposition, a little like he was underwater and trying to get to the surface. He was not quite drowning, not yet, but air seemed a long way off.

“Nothing,” Christopher said.

“Hmmm?”

Christopher took William’s money and put the book in a brown paper bag. Then he took the Munchies wrapper out of the waste bin and put it in the cash register just to be sure.

Billy Moon © Douglas Lain 2013

I am more than half way through the book Billy Moon by Douglas Lain, excellent – the timing for publication couldn’t have been better as in 1968 – people here in the U.S. & everywhere in the world have been speaking out against US military strikes against Syria. A revitalization of the anti-war & peace & justice movements are growing. There is much to be gleaned from this fictional look back at our broken history, what inspired, what worked, what didn’t. There seems to me to be a lingering question – why didn’t it set the world rightside up? Maybe the answer is, there are more chapters to this story than anyone ever expected. Life is always just a beginning there is no end, the end of an actor in the play of life dies and leaves the stage but the stage & the play continues, each act just another beginning. Are we looking for the end or a utopian theme? What is our goal, how would we write the script, what characteristics would we ascribe to ourselves? Who are we, what would we do if fascism creeped into our everyday lives? Would we be revolutionaries, zombies or collaborators? Well believe it or not fascism is on your doorstep, it is time for you to decide what actor/character you will bring to the stage.